Bethnal Green’s LTN divide – are the most deprived shouldering the burden of traffic?

In front of a packed town hall on 20 September, Lutfur Rahman, The Mayor of Tower Hamlets, announced his intention to remove the road closures introduced as part of the Liveable Streets programme.

Rahman’s decision was founded on the idea that the programme was perpetuating class inequality in the borough and fuelling division in its communities.

The Mayor, explaining his rationale to a Cabinet meeting, argued that the road closures were having an inordinately adverse impact on working-class residents by, ‘push(ing) traffic down surrounding arterial roads, typically lived on by less affluent residents’. But was this true? Was Liveable Streets cementing class inequality in one of London’s most unequal boroughs?

Divisive measures

What would become the source of an acerbic fissure in the community began with the unremarkable appearance of road closure signs on Punderson’s Gardens, Pollard Row, Clarkson Street, Teesdale Street, and Canrobert Street as well as the emergence of a large crater in the middle of Old Bethnal Green Road in June of 2020.

When Spencer, a local construction worker, saw the road closure signs he was delighted, at first, believing the news was, ‘…too good to be true.’ Spencer, who lives between Hackney Road, a boundary road, and Columbia Road, had been stressed by noise and pollution from through traffic for years.

Speaking to this magazine, Spencer recalled life before the road closures, ‘The last night before the road was closed outside of my house, these cars came… playing loud music at 1 a.m… speeding down around the corner at 100 miles an hour, and I thought… this is exactly what needed to stop. Then the next day, it had stopped. It just stopped… like someone had pressed an off button.’

Throughout the second half of 2020, these road closure signs would give way to small construction sites, which would in turn give way to permanent physical changes in the streets themselves.

Five bollards and a birch tree were planted in the centre of Punderson’s Gardens, previously a two-way street connecting Midleton Street to Bethnal Green Road.

New footpaths were laid to close the junctions of Ivimey Street, Pollard Row and Pollard Street. Red planters appeared along Pollard Row, and the footpath was widened and embellished with a sycamore tree and little plots of gardens adorned with shrubs and flowers.

At the Ellsworth Street end of Clarkson Street, the footpath was widened, narrowing the road to ensure that only bicycles could pass the length of the road.

Where Teesdale Street leads out onto Old Bethnal Green Road, paving stones have been laid over the tarmac and additional parking spaces for bicycles, a planter, seating and five bollards now block off the junction. These measures collectively compose what is termed a “pocket park”.

Another of these pocket parks was created to seal off the junction of Canrobert Street and Old Bethnal Green Road.

Old Bethnal Green Road itself was undoubtedly the street most transformed, for better or worse (depending on who you ask), by these myriad changes. The road, which used to function as a busy two-way thoroughfare connecting Cambridge Heath Road to Gosset Street, was closed altogether to eastbound traffic at the bottom of Clarkson Street. The tarmac road has been replaced by paving, bollards, plants, trees, and bicycle lanes.

The western end of the road, from Gosset Street, was made one way as well, diverting traffic coming from Hackney Road and Gosset Street up Temple Street, rendering it impractical for non-local motorists to use Old Bethnal Green Road as a short cut to get onto Cambridge Heath Road. Paving stones, plants and a bicycle lane which ran from Mansford Street to Clarkson Street, took up the newly obsolete side of the road.

Not everyone was happy with the new look Bethnal Green. When Kim, the owner of Tiki’s hairdressers on Old Bethnal Green Road, saw the road closure signs, she began to worry about her business, which she says has lost footfall since the introduction of the measures. Kim, speaking to this magazine, said that she felt, ‘sad’, and unheard a’ “most of the shopkeepers were never asked or advised on what was going to happen.’

Other measures followed; the Gosset Street and Columbia Road junction was replaced with a mini public plaza outside the Birdcage; Columbia Road was made one way between Chambord Street and Ravenscroft Steet; Ravenscroft Street was made one way; a camera and planters were installed to stop cars from passing down the junction at Barnet Grove and Wellington Road; Old Nichols Street junction was closed, and Arnold Circus was partially closed alongside restricted access to streets on the Boundary Estate, one of London’s oldest housing estates. The West end of Quilter Street was also closed along with the junction at Derbyshire Street and Vallance Road.

Liveable Streets Scheme

Each of these initiatives was a piece in a jigsaw of measures designed to keep non-residential traffic from passing through the Bethnal Green area. The measures were also intended to make driving short distances more complicated for residents to encourage them to walk and cycle instead.

Introduced as part of the Liveable Streets programme, the initiatives had been introduced with the aim of turning Bethnal Green, and up to 60% of Tower Hamlets, into Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs).

According to council documentation, Liveable Streets was ‘…a multi-million-pound borough-wide street and public space improvement programme.’ In Bethnal Green alone, a total of £3,531,503 was eventually spent on the measures.

The programme’s stated goal was ‘to reduce people making short-cuts through residential streets to eliminate “rat runs” and encourage more sustainable journeys to improve air quality and road safety.’

The majority of the measures proposed by the programme were never actually implemented in the borough’s designated areas. Bethnal Green was a notable exception, however. Almost all (80%) of the proposed elements of the scheme were enacted here; successfully transforming the area into another of the many Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) springing up around the UK.

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods

Anyone who has opened a newspaper over the last nine months will have heard of an LTN and will likely know that Tower Hamlets was not the only local authority to have introduced the schemes in the UK. Since the pandemic, LTNs have been established the length and breadth of the country and been subject to endless coverage from local and national media.

A Guardian article in May revealed that, in the first 19 weeks of 2023, the UK’s main newspapers had already published 177 articles on LTNs. Most of these pieces were unfavourable and published in the Mail (75), the Telegraph (32) or the Times (22).

The coverage has often felt sensationalist, as is perhaps best illustrated by a BBC article which labelled the schemes ‘more divisive than Brexit’, despite the fact that recent polling showed only 17% of London’s residents, (where most of the schemes have been implemented) oppose the blocking of residential streets to rat-running motorists.

LTNs, aided in no small part by the media, have been subsumed into the culture wars. People have taken sides, completely disavowed the legitimate concerns of those of the opposing persuasions, and consequentially become deeply entrenched in their own views. This has led to polarisation in communities across the UK and left no space for the creation of a general consensus or compromise on the issue.

Yet in essence, an LTN is just an urban planning concept that attempts to reduce traffic and improve conditions for pedestrians and cyclists in residential areas. If properly implemented, the schemes should restrict through-traffic while continuing to allow access to residents, businesses, and essential services.

The schemes have been in place in London since the 1970s, however, their rollout was accelerated during and in the wake of the pandemic.

The catalyst for acceleration came in May 2020 when the government published statutory guidance urging councils to reallocate road space to cyclists and pedestrians.

The state concurrently announced a £250m ‘emergency active travel fund’, which was the first part of a £2bn central funding package, aimed at creating a ‘new era’ for cycling and walking in England as well as capitalizing on the drop in pollution instigated by the pandemic.

The policy had the desired effect, and in the six-month period between March and September 2020, a total of 72 LTNs had been created in London alone.

The proliferation of the schemes cannot, however, be wholly attributed to government policy. The implementation of any given LTN is a collaborative effort involving the government, mayors, local councils, communities, and various other stakeholders.

On a London level, LTNs are a key facet of Sadiq Khan, the Mayor of London’s, broader strategy to address traffic congestion, air pollution, and to create more liveable communities. Khan, who has been proactive in his quest to reduce emissions in the Capital, has developed a strategy involving an alphabet soup of car-reduction policies. This alphabet soup includes measures such as LTNs, ULEZ, LEZ, and the now defunct T-Charge.

Khan provided various supports to encourage the implementation of LTNs across London during his tenure, offering funding, logistical assistance, guidance, as well as public backing of the measures.

In most instances, LTNs have not faced the same opposition as ULEZ, which has prompted a hunger-strike, inspired widespread attacks on traffic infrastructure, triggered high court challenges and acted as a deciding factor in the by-election in UxBridge.

In Tower Hamlets, although seemingly widely supported, LTNs have undoubtedly been the most schismatic of these car-reduction policies.

A community divided by traffic

The schemes were introduced in October 2019, when Tower Hamlets Labour-led cabinet approved the Liveable Streets programme, which pertained to 17 projects, one of which was in Bethnal Green.

The Labour-led Council, buoyed up by a resoundingly positive result in the consultation process – 68% of respondents supported the proposal – pushed the measures through.

In May 2022, Aspire, the left-wing independent party, took power, making Tower Hamlets the first local authority in London to elect a party that was not Labour, Conservative or Liberal Democrat in almost 60 years.

In their manifesto Aspire had promised to scrap the schemes that were deeply unpopular with their core British-Bangladeshi voter base.

The newly elected party held another two consultations soon after taking office, both of which showed a majority in support of the schemes. However, these consultations were less emphatically supportive of the measures and told the tale of a divided community.

Responses in the 2022 consultation showed that 50% of residents wanted to keep the schemes, down from 68%, while 47% wanted them removed.

In the third consultation held in January 2023, support was stronger, with 57.3% of residents backing the retention of the schemes, however, opposition remained strong, particularly among the communities large British-Bangladeshi population, 94.1% of whom wanted the closures removed.

LTNs: cementers of class inequality?

Despite the community’s consistent support of the measures, Aspire pressed ahead with their removal in late September of this year.

Speaking to this magazine about their decision to scrap the schemes, an Aspire spokesperson argued that, despite the results of the consultations, the party had mandate for the schemes’ removal on account of their victory in the election.

‘Ultimately, opposition to LTNs was a key issue – maybe the key issue – in the 2022 Mayoral and Council elections, which saw Lutfur Rahman elected with just under 40,000 votes, and the Aspire Party gaining an outright majority of seats in the Council chamber. The democratic will of residents must be respected. Equally, we must find more universal and egalitarian ways of reducing air pollution and addressing the climate emergency in London and beyond.’

The spokesperson went on to explain the party’s rationale for scrapping the schemes;

‘The Aspire Party believes in finding more inclusive and widely accessible solutions to reducing toxic air pollution in Tower Hamlets – solutions that do not push costs onto our most disadvantaged residents, as LTNs have.

Research shows that, while LTNs improve air quality in their immediate vicinity, they push traffic down surrounding arterial roads, typically lived on by less affluent and BME residents.’

Aspire’s line of argument, that the implementation of LTNs is cementing class inequality by displacing more traffic away from affluent inroads onto major arteries where people on lower incomes are more likely to live, is arguably the most compelling argument made in opposition to LTNs, but is it true in the case of Bethnal Green?

The burden of traffic

The Bethnal Green LTN is hemmed in by Hackney Road to the North, Cambridge Heath Road to the East and Bethnal Green Road to the South. These three roads, according to Rahman’s hypothesis, are soaking up the traffic displaced by the imposition of the Bethnal Green LTN.

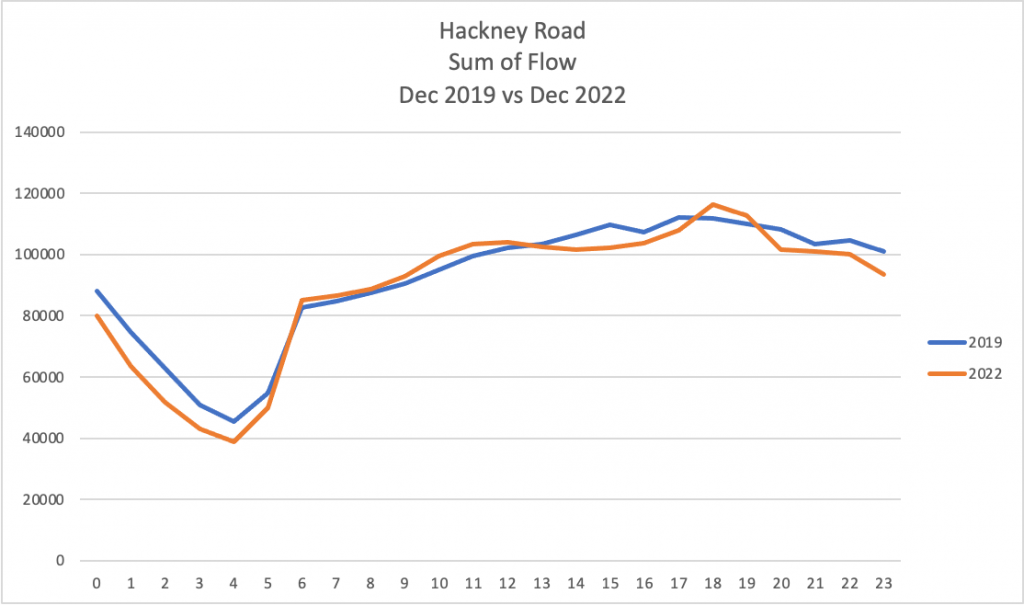

SCOOT data provided by TfL works to undermine Rahman’s claim in relation to traffic levels on Hackney Road.

A comparison of the data from a count point situated where Hackney Road meets Queensbridge Road shows a 7% decrease in traffic flow from an average daily flow of 17,317 in December 2019 to 16,175 in December 2022.

It must be noted, however, that SCOOT data can be at risk of inaccuracy in peak traffic as it is derived from sensors on traffic signals and is not equivalent to an actual traffic count. It does, however, provide a useful approximation.

Evidence gleaned from an automatic traffic counter on Bethnal Green Road, on the southern boundary of the LTN, produces findings which offer some tentative support to Rahman’s hypothesis that the LTN is displacing traffic onto boundary roads.

On Bethnal Green Road the average daily traffic count was 16,032 in 2018, before the LTN had been implemented, but by 2022, post-LTN, this had increased slightly to 16,737. Almost all of this increase came from an increase in traffic travelling Eastbound, out of the city.

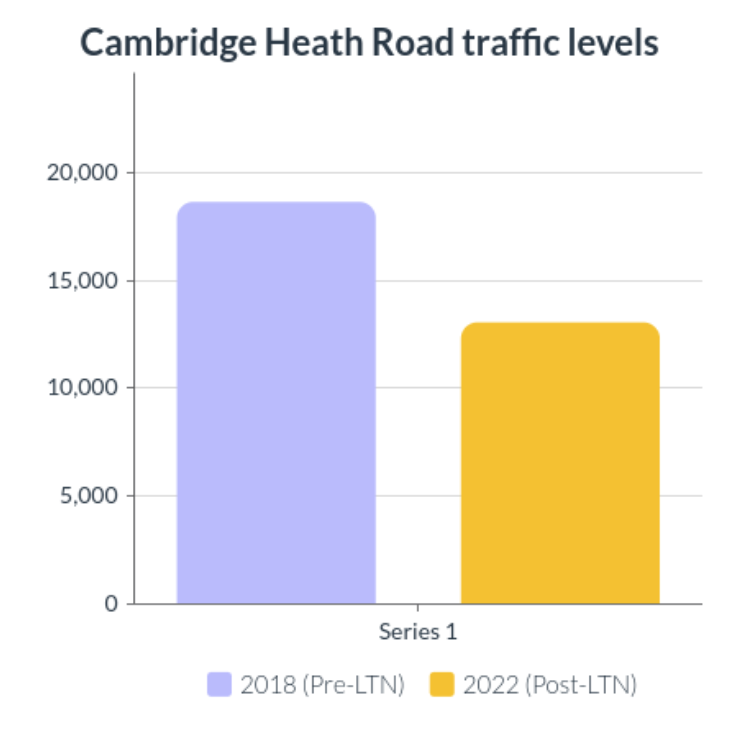

On Cambridge Heath Road, manual counts by the Council showed that there had been a market decrease in traffic from pre-LTN levels of 18,654 cars a day in 2018 to 13,065 in 2022. The revelation of a 30% reduction in traffic, a much greater reduction than the negligible increases on the other two boundary roads, works to significantly undermine the narrative of Aspire.

Evidently, other factors such as the introduction of ULEZ and long-term changes in modes of travel instigated by the pandemic’s disruption of established travel patterns, must be considered as factors in this dramatic reduction as well.

These findings show that residents of Bethnal Green Road and Hackney Road were experiencing negligible changes in traffic levels, while residents of Cambridge Heath Road were enjoying a significant reduction in the number of cars that passed down their road in the wake of the LTNs introduction.

The dramatic reduction in traffic levels on Cambridge Heath Road would indicate that the schemes were contributing to a reduction in traffic for residents of one of the boundary roads, while having minimal impact on residents of the other two boundary roads.

However, a look at the congestion and delay data reveals the more complex reality of the situation.

The millstone of congestion

On Hackney Road, between early 2020 and 2022, although traffic levels had only increased slightly, congestion had increased by the significant margin of 20% in the peak hours of 4-7 p.m.

According to Department of Transport data there had also been a 60% increase in delays on Hackney Road from 2019 to 2021, denoting a significant increase in congestion.

Residents of Hackney Road are also dealing with displaced traffic from the Hackney LTN, which is one of the most expansive LTNs in the U.K.

Data from the Department of Transport showed that there had been a moderate increase of 13% in delays on Bethnal Green Road between 2019 and 2021. Congestion had also increased by 16% on Bethnal Green Road between December 2019 and December 2022 according to SCOOT data.

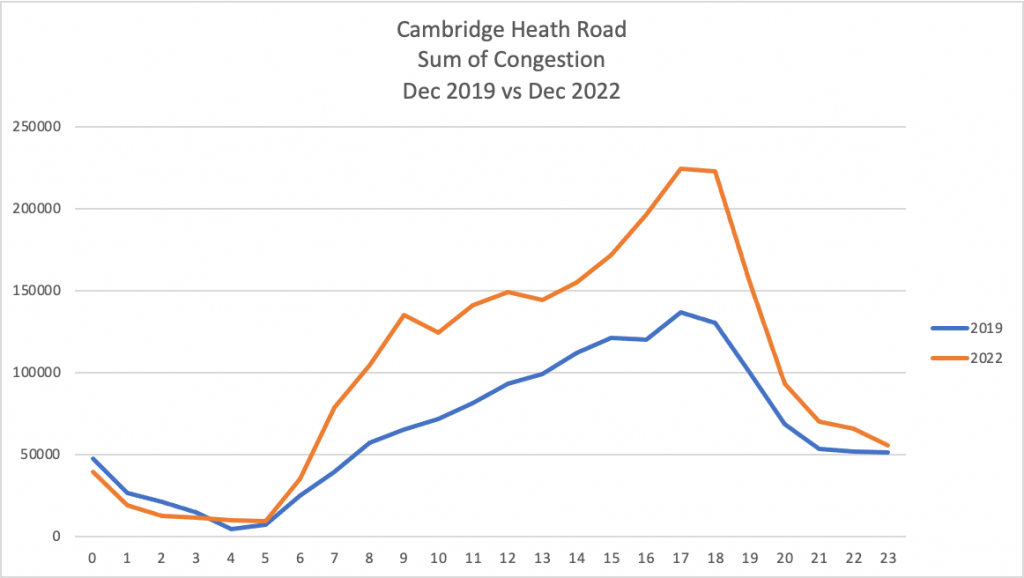

Data gleaned from SCOOT count points on Cambridge Heath Road showed a dramatic 51% increase in congestion from December 2019 to December 2022.

So, although the LTN had had minimal impact on traffic levels on two boundary roads and reduced traffic along one, those living on all of the boundary roads were being affected by increased congestion and delays, and quite drastically so in peak time traffic.

Even though the number of cars passing down the boundary roads each day was not rising, more vehicles were now using the roads at peak hours, bringing the road to its capacity and causing congestion and delays in peak hours.

The increase in delays and congestion was moderate on Bethnal Green Road, and severe on Cambridge Heath Road and Hackney Road, which was under pressure from its position sandwiched between LTNs in Hackney and Tower Hamlets.

Rahman’s argument that traffic was being displaced onto boundary roads was overly simplistic in that daily traffic volume had, on average, decreased on these roads, but his belief that residents of boundary roads were being affected negatively by the schemes can derive some legitimacy from the fact that congestion and delays had increased overall on the boundary roads.

In reality, Liveable Streets had been successful in contributing to the greatly reduced levels of traffic on the Cambridge Heath Road and it had not, in any drastic way, displaced traffic onto the other two boundary roads. However, the increase in congestion and delays on all boundary roads, particularly in peak hours, would indicate that the scheme needed to be tweaked or at least given time to settle.

Still, the decision to scrap the scheme, before attempting to alter it, will be difficult to swallow for many in a community in which the programme was generally supported.

It must also be noted that the Liveable Streets scheme had undoubtedly fomented intense opposition within a sizable section of the community as well. This division, which the Mayor of Tower Hamlets had cited as one of his reasons for ending the schemes, was in no small part aided by consultation processes which were considered unfair by residents.

Consultation concerns

Local residents, of both persuasions, repeatedly told this magazine that their anger was stemming from a feeling that decisions were being imposed upon them against their will, and that the consultation processes had not properly accounted for their opinions.

A spokesperson from pro-LTN group, Save our Safer Streets, told us that her group had, ‘many issues with Aspire’s consultation process’, arguing that the Council’s consultation documents, ‘presented highly skewed and misleading information.’

The first consultation process, led by Labour, also attracted criticism.

Nick, a local resident of Jesus Green, said that ‘it seemed like the whole consultation process was skewered to get the result that PC Consult (consultants who ran the first consultation) wanted.’

Nick argued that the language used on the consultation surveys was problematic as it implicated that if the community wanted infrastructural improvements such as ‘tree planting, wider footpaths, additional lighting and CCTV” they also had ‘to support road closures.’

Labour Councillor Gabriel Salva Macallan, speaking in a Council meeting, argued that it was the approach of the Council, of which she was a part, that was fuelling this division, ‘It is how we approach this as a council that has polarised people’ Macallan said, arguing that the fault lines of class were not properly addressed in the consultation process, ‘We need to talk about class and gentrification.’

The first consultation

PC Consult (PCC), the design, engineering and landscape architecture consultancy firm appointed by the Labour led Council to run the first engagement process, have taken heavy criticism from all angles.

PCC’s process involved receiving online feedback from the community, creating an interactive map, running drop-in sessions, and holding meetings with councillors and community groups. The local community were also invited to two workshops where attendees were presented with plans showing suggestions to improve the area and tackle issues based on feedback from the early engagement.

In October and November of 2019 drop-in sessions were held, consultation packs were delivered to over 10,000 addresses and the community was asked, online and via physical forms contained in the consultation packs, for its views on the final designs. 2,036 individuals responded to the survey.

Emergency services, council departments, Safer Neighbourhood Teams and Transport for London were also liaised with by PC Consult throughout the project.

However, according to the testimony of local councillors, and council documents displayed at an Overview and Scrutiny Committee meeting in 2021, the consultation and engagement process was riddled with problems.

The documents noted that the process had failed to gain the trust of “certain sections of the community” on account of a perception “that the project is led by a team of external consultants.”

In the most recent Cabinet meeting, Peter Golds, Conservative Councillor, echoed similar concerns about the consultations failure to reach working-class residents of tower blocks.

Additionally, the documents included the assertion that the process should have been, “less reliant on online responses and mailed out surveys” and that feeling toward the scheme “needs to be captured in a more face to face way to address digital exclusion concerns.”

The papers recognized that the “survey design needs to be simplified to make it more accessible, e.g., less text and limited use of jargon” and that “systems need to be in place to address potential abuse of online responses from interest groups” after responses, “were received from other parts of the UK.”

Wasted millions

The Liveable Streets scheme had succeeded in reducing traffic on the boundary roads surrounding the Bethnal Green LTN, but also contributed to increased delays and congestion.

Aspire can justify their removal of the schemes through reasoning that the increased congestion on boundary roads is negatively affecting the lives of the more deprived residents of these roads.

However, the Council’s failure to even attempt to tweak the schemes via the use of ANPR and other measures more palatable to all residents has left a sour taste in the mouths of many Bethnal Green residents, who generally supported the schemes.

In reality, it is likely that Aspire’s decision was made on behalf of their British-Bangladeshi voter base, 94% of whom oppose the road closures.

The decision not to listen to the majority of respondents in Bethnal Green and to fail to attempt to bridge the divide by tweaking the schemes will enflame the discontent of pro-LTN residents, and only added fuel to a divide that has been worsened by failures in governance from the inception of the scheme.

In the end, it was not solely the more deprived residents of the boundary roads, or the pro-LTN residents who ended up losing out, but instead all residents of Bethnal Green who missed out on millions of pounds worth of investment in their community.

LTNs can look pretty but the road closures meant ambulances couldn’t get through, drivers were getting stuck down roads, drugdealers were hiding gear inside the giant plant pots, no one was looking after the trees/plants which were suffering and dying in those ugly wooden crates… the experience is not and was not nice.

The blue bike lanes near where I live are almost always empty. Am not a biker as I can’t get all my work stuff nor weekly shopping onto a bike.

The Labour Council were failing to put the citizens first. I don’t trust the Council officers from leafy Shires making top-down decisions for everyone.

Why don’t they grow a forest on public land instead of tower blocks full of luxury flats?

In the Netherlands they just pushed forward with a pro-cycling campaign. A road should be a road.

Very interesting to see the analysis of traffic on boundary roads in this article.

If there is too much traffic on A-roads like Bethnal Green Rd and Hackney Rd, what is the solution? The council wants to just let that traffic spread out to small, residential roads like Columbia Rd and Old Bethnal Green Rd. But these streets were not designed to handle so much traffic. They are not A-roads. They are narrower, have narrower pavements and no traffic lights. They are not lined with businesses; they are lined with high density housing – including a lot of social housing and what the article might call “deprivation”. They are lined with schools; I counted 7 in the LTN area!

In short, residential roads are designed for local access. And for this, the LTN is fully open. Anyone can drive to their address. No one is cut off. They are also meant to be for walking to the shops, for kids walking, cycling and scooting to school, and for the elderly to feel safe coming out of their homes to go for a walk and socialise with neighbours.

There is definitely an issue with too much congestion on A-roads. But the solution can’t be to make smaller roads more unsafe for everyone. We can do better than that.

The LTN’s have created segregation within our communities as I live and work in Bethnal Green and as a working class family we are more deeply impacted. It is disproportionately pushing the burden into the less affluent communities from the affluent areas. I also work in Roman Rd and same is also happening there, where segregation of who gets impacted the most depends which areas you live in. In one instance a lady from the affluent area told me how kids from her area can safely walk around their and play safely. When I mention “what about the other areas” she replied “oh you mean the council people”, its self-explanatory what she meant.