A peruse of Princelet Street’s migrational past and present

Princelet’s Street’s Huguenot history is legendary, but a walk down this gorgeous Georgian street reveals signs of other migrant communities that have formed the identity of the East End.

Stumbling eastwards across the cobbles from Spitalfields Market, I head down a narrow alley I would have missed if it hadn’t been aglow with graffiti. Tracing the neon scrawls along the passage, I come to an open intersection and a choice of roads. It’s easy to spot Princelet Street thanks to its picture-perfect Georgian architecture.

Blackened iron street lamps tower along either side of the road and bow to the even taller brick houses that loom into the clouds. The warm, weathered bricks of the houses appear seamless and form two impenetrable terraces with exits only at either end. Terracotta chimneys protrude from every roof, resembling castle parapets. Standing in the middle of the one-way street, it feels as though you’re between two fortress walls.

It’s quite an imposing sight.

However, Princelet Street is much less of a fortress than it is a refuge; throughout its lifetime it has provided a home and protection to generations of migrants.

Standing at the end of the street, I look up and admire the wide ray-catching windows atop each house. From the late 19th Century, French Protestants – Huguenots – escaped the prosecution of Catholic France and found homes in the streets of Spitalfields. On Princelet Street in particular you can see evidence of how they altered the windows to enable great light into their top-floor silk-weaving studios.

Spitalfields is famous for the silk weaving industry that boomed during the 18th Century and Princelet Street was at the heart of it. An English Heritage blue plaque on the end-of-terrace building reads ‘Anna Maria Garthwaite 1690 – 1763 Designer of Spitalfields Silks lived and worked here’; A pioneer of botanic silk patterns, Garthwaites’ designs can be found in the Victoria and Albert Museum today.

I head down further, curious to discover the other houses’ histories.

There is uniformity in the terraced housing, yet each building is distinct. Windows are framed in red bricks, now faded to shades of burgundy and brown, and doors are either arched or squared and bear unique decorative door knockers. In recent years many of these Georgian townhouses have been lovingly restored to preserve their original features and exude an expensively modest charm.

A guide leads a tour group of teens down the doorways. I linger behind as he recounts to the group about London’s first Yiddish Theatre at No. 3. Suddenly yelling “fire!” and waving his arms ludicrously, the guide enacts the downfall of the theatre in 1887 when someone falsely tricked the audience to evade an imaginary fire, causing a stampede that killed 17 people as well as the theatre’s reputation.

It’s hard to imagine as the building has since been rebuilt and the front wall is now made almost entirely of glass.

It’s one of a handful of houses on the street that provides a contrast to the highly preserved Georgian architecture. With the harder lines of perfectly angled modern bricks, and steel door frames a few buildings have evidently been repurposed as studios or office spaces.

Another heritage plaque peeking down above the green-tinged windows of No. 17 entices me across the street. It was the birthplace of Miriam Moses, the first female – and female Jewish – Mayor of Stepney.

Next door, at No. 19, a tiny piece of paper taped to the window tells us this is the Museum of Immigration and Diversity – ‘Europe’s first’ the paper declares – revealing part of its 300-year-old history.

Evident from the widened attic windows above, No. 19 once housed a silk studio for a Huguenot family in the early 19th Century. Later, 19 Princelet Street became a space of solace to the Jewish community; a settlement for the Jewish Friendly Society and a place to safely meet for the anti-fascist movement. In 1869, a synagogue was even built in the garden.

The museum was closed and is only open by appointment. The house has been preserved as a space that explores the theme of belonging. A recent exhibition “Suitcases and Sanctuary” was created by local school children whose families have moved to the area more recently, from Bangladesh, the Caribbean, Somalia, Kurdistan and more.

Across from No. 19 is the faded ghost of a shop sign, the ‘Modern Saree Centre’. The building now appears to be an office, so with the sarees long gone, I’m left wondering if the shop had its heyday in the 1970s, when Spitalfields saw a large wave of migration from Bangladesh.

Since a change in UK immigration law and the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, the streets surrounding Spitalfields have been home to a Bangladeshi community, now the largest ethnic group in Bethnal Green.

On a nearby doorway, two stick figures are spray-painted. One wears a burka, the other smiles, and together, they hold hands. I instantly recognise this as the work of Stik, a London street artist.

Garish and bold on Princelet’s aged bricks, the scrawls and swirls of the graffiti have crept from around the corner. I look up to the street name drilled onto the wall, once in English, and again in Sylheti, the main language spoken by the East End Bengali community. Also from around the corner wafts a deep musk of a tantalising masala spice. My stomach pulls me along the pavement towards the possibility of a succulent tomato sauce smothering a bed of pilau rice where Princelet Street intersects Brick Lane.

Standing in the middle of the crossroad, I take stock of the shops on the corner, each representing the current residents of the area nicely. There’s the Eastern Eye Balti House serving London foodies authentic Indian and Bengali food. There’s a vape shop, lined with sweety flavoured vapes for the younger shoppers on the search for vintage clothing bargains. There’s an ice cream shop for sweet-toothed tourists. And, a cocktail bar for the affluent twenty-somethings moving to the fashionable East End from the City and further West.

I leave Brick Lane behind and peruse the other side of Princelet Street. The balti houses’ spiced tang is replaced by a whiff of a lighter, herby aroma. Just behind the ice cream shop is a painted black shop bursting with greenery.

In a gritty urban environment, Jen’s Flower Shop provides a bit of nature. The fresh scent of Princelet’s jungle is alluring and I step inside. Hanging from the ceiling are sprigs of drying flowers, and below, shelves upon shelves of spiked cacti. I cautiously step around pots of sage green saplings on the floor and peer around blooming bouquets on the shop counter to find Jen, who is as vibrant as her flowers. Rosy-cheeked, Jen asks if there is anything she can help me with. Seduced by the sweet perfume, I leave with a wrapped bunch of peonies under my arm.

Stepping back out onto Princelet, this side is quieter than the other, perhaps more commercial. If you harboured an itch to explore even further afield, you’ll find a rare thing here – bricks-and-mortar travel agents. Two of them. There is also a print and photocopy shop, a tattoo parlour and Iqbal Gents Hair Styling. Seeing the number of locals entering the shop in the short time I was there, Iqbal’s appears to be more than just a barber’s, more of a social hub.

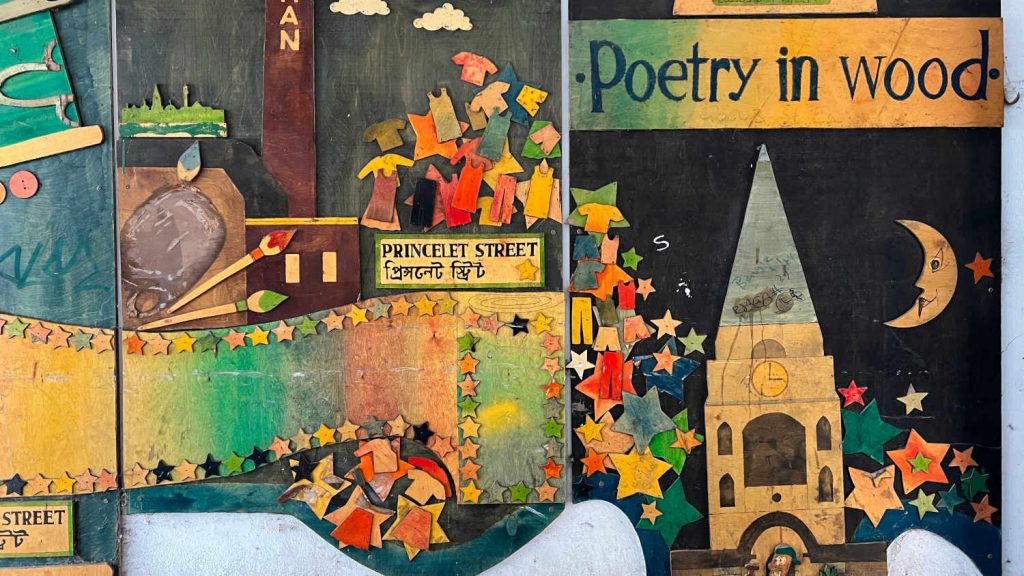

Glimpsing a stroke of golden paint through the door, I wander into a side alley. And I’m really glad I did. I find a Spitalfields map, formed of multi-coloured brushstrokes on wooden canvas that takes up the whole wall. It highlights the streets significant to the Bengali community including, of course, Princelet Street.

Not as ostentatious as the graffiti that demands a reaction towards Brick Lane, I feel grateful to have found this mural hidden behind the closed door.

I trace the pathways of the mural into an open courtyard, where a gentle buzz of voices rises. They are coming from a small, single-storey white-painted building nestled in a courtyard behind Princelet’s townhouse towers. It’s the Bangla Press Centre, a charity supporting Bangladeshi media. Inside, a group of men chat jovially in small clusters. A cough of a clearing throat silences the babbles and commences what appears to be a meeting.

My cue to leave, I say goodbye to the streets of Spitalfields in sketch, and back onto the wider road.

I look back on Princelet Street. The Bangla travel shops, Jen’s flowers, the Balti house, the blue plaque on the townhouses: each door a marker of refuge, struggle, safety, connection, and belonging.

Travelling down Princelet Street is like walking through time and experiencing the movement, integration and solidarity of migrants and communities that have shaped and continue to shape the East End and Bethnal Green today.