The Joiners Arms: from “let’s save this one gay bar” to “let’s save queer spaces”

Friends of the Joiners Arms is pioneering accessible and inclusive queer spaces, against the backdrop of the ongoing mass closure of LGBTQ+ venues across London.

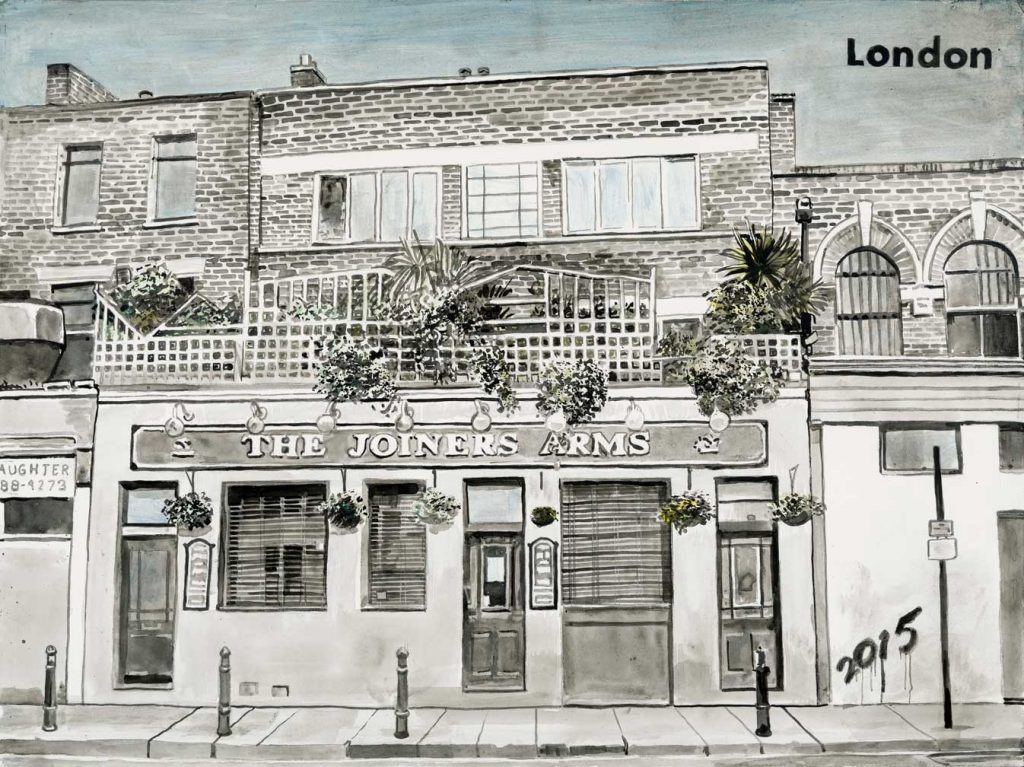

Jon Ward went to the Joiners Arms one evening in late 2014 for drinks with a group of friends. A queer pub on Hackney Road, the Joiners was a short walk from Hoxton overground station and just above the west end of Columbia Road. After chatting to somebody at the bar in the ‘normal sort of boozy, friendly way of the Joiners’, Jon was told that the space would soon be closing down.

‘I was pissed off that a queer space was going to be lost for a luxury hotel,’ Jon says. ‘Hackney Road was super gentrified already, it’s not what the local community wanted or needed.’

There was a strategy meeting happening at the pub to decide on the best way to campaign against the developers, which Jon eagerly joined.

Between 2006 and 2016, 58% of LGBTQ+ venues across London closed down- a number which is still rising. The lazy rhetoric around the disappearance of these spaces, says Jon, is that there’s not enough demand.

However, as a UCL research project indicates, the actual reasons behind the closures point more towards the wider effects of gentrification in the city: the negative impacts of large-scale developments on venue clusters, rising business rate and rents and changing ownership leading to the targeting of non-LGBTQ+ clientele.

First established in 1997, the Joiners Arms was more than just a pub – it was an LGBTQ+ space that welcomed people from all walks of life, as well as hosted discussions, exhibitions and fundraisers.

Class is something that is often forgotten about in supposedly inclusive queer venues, but landlord David Pollard was passionate about queer spaces being cornerstones of working class communities. It was even the first pub to pay the living wage.

However, the Joiners Arms was not without fault. Jon and Izzy (another member of the Friends of Joiners Arms campaign group) tell me that it wasn’t the most inclusive place in terms of gender; on the whole it was dominated by cis gay men, with a tendency to be ‘cliquey.’

The campaign group fiercely lobbied Tower Hamlets to keep the Joiners Arms open, fighting hard to keep this stalwart of east London’s queer community alive. Despite their best efforts, they were unable to save it.

The Joiners Arms was a part of a triangle of LGBTQ+ venues in the area, with the Nelson’s Head near Columbia Road and the George and Dragon also on Hackney Road. Sadly, all three venues closed in early 2015.

Although they were unable to stop the Joiners from closing, the campaign group managed to achieve ACV status, rendering the Joiners an ‘Asset of Community Value’. This meant that the council recognised the Joiners Arms had been of ‘real use’ to the local community.

This was significant in being able to leverage power; as the developers caused a loss of a community asset, they had to make sure it was replaced. It was a, ‘complete pain in the ass for developers,’ Jon says. ‘Which was a total win.’

The actual building of the Joiners went through many difficulties concerning planning permission: the developers’ plans were initially rejected and then the pandemic hit. The building itself currently remains empty.

Not succumbing to the loss of the original building, the Friends of the Joiners Arms started to think bigger and better. They were curious as to what else could be created, as well as how to build a queer community and pragmatically and logistically build what they considered to be important in queer venues.

‘The idea was to take the spirit of the group who were bemoaning the loss of the Joiners,’ Jon says, ‘whilst also talking about larger issues, like gentrification and the broader loss of queer spaces across London.’

‘The campaign is now about queerness in all its glory; the complete diversity of the queer and trans community coming together,’ Izzy tells me.

The Friends of the Joiners Arms have been delivering a programme of events at nearby venues to help build a following and create engagement with the campaign while they worked on getting a permanent space.

One of their regular events is Lèse Majesté, a drag cabaret night which prioritises trans men, non-binary people and performers of colour, held at Bethnal Green Working Men’s Club.

The group remain conscious of their roots: as the Joiners Arms played a central role in east London’s queer community, they are keeping the area at the heart of the campaign, and aim to find a new place to serve the same geographic community.

What is striking about Friends of the Joiners, and is clear when Jon and Izzy speak emphatically and passionately about the campaign, is their commitment to complete inclusivity, diversity and speaking up for the most marginalised parts of the queer community, which are often overlooked.

Part of this was recognising the huge scarcity of venues which are completely accessible. ‘We began to think about who we weren’t reaching with our events like Lèse Majesté,’ Izzy tells me.

They started working with the Outside Project: an LGBTQ+ homeless shelter. They ran a few sober Lèse Majesté nights, free of charge and aimed at people who didn’t want to go out at night.

This kickstarted their journey into becoming more accessible. ‘They were our first foray into victory, Izzy says. ‘We started to understand how to deliver to people with access needs that we don’t share, and require a physical change in the space.’

From there, they’ve worked with Quiplash who do accessibility training and audio description; consequently employing BSL interpreters at their events. They’ve also been trained in providing for people’s accessibility needs, such as giving information on how many steps there are into the venue, or letting people know exactly where there’s parking.

In creating wholly inclusive spaces, the question is raised of whether non-LGBTQ+ people should be included in spaces which are created specifically to protect the queer community.

‘If straight people want to come along that’s great, but we also encourage people to be mindful of how the space is specifically for folks who face marginalisation, oppression and violence. But if those aren’t your experiences, then you should maybe give space over to others,’ Jon says.

The issue of surveilling people on the door; asking them what their identity is, or asking people questions to demonstrate that identity is obviously a huge issue, continues Jon. ‘I think a lot of the ways that they come up with solutions are super problematic, and that’s definitely not our way of doing things.’

The last eight years have been incredibly challenging for the campaign group, as they have battled developers and navigated the hostile environment of the constantly gentrifying city.

‘The campaign started as “let’s save this one gay bar”, and then it turned into “let’s save queer spaces,” Izzy tells me. ‘Now we’ve realised that your struggle is my struggle and we’re all facing the same challenges.’

‘That’s why we’ve integrated it as a fight against gentrification more generally, whether that’s housing, or whether that’s things like the Save Brick Lane campaign, or the Save Ridley Road; they’re all facing the same powers that we are, so we’re striving towards working together as much as possible.’

Their community shares crowdfunder is still over £40,000 short of the target they need in order to establish a permanent space. If you would like to invest in the campaign, you can buy a community share through this link.

If you enjoyed reading this you might like our piece on local artist Milou Stella.